Volume. 7 Issue. 13 – April 12, 2023

A 1994 claim that was reopened in 2015 almost 20 years after initial closure, is featured this week. The insurer’s actions/inactions in the subsequent five years since reopening the case ultimately resulted in over $150K in ACB being awarded, plus $17K in treatment plans, with an award approaching $85K.

LAT Update – What Difference Did A Year Make?

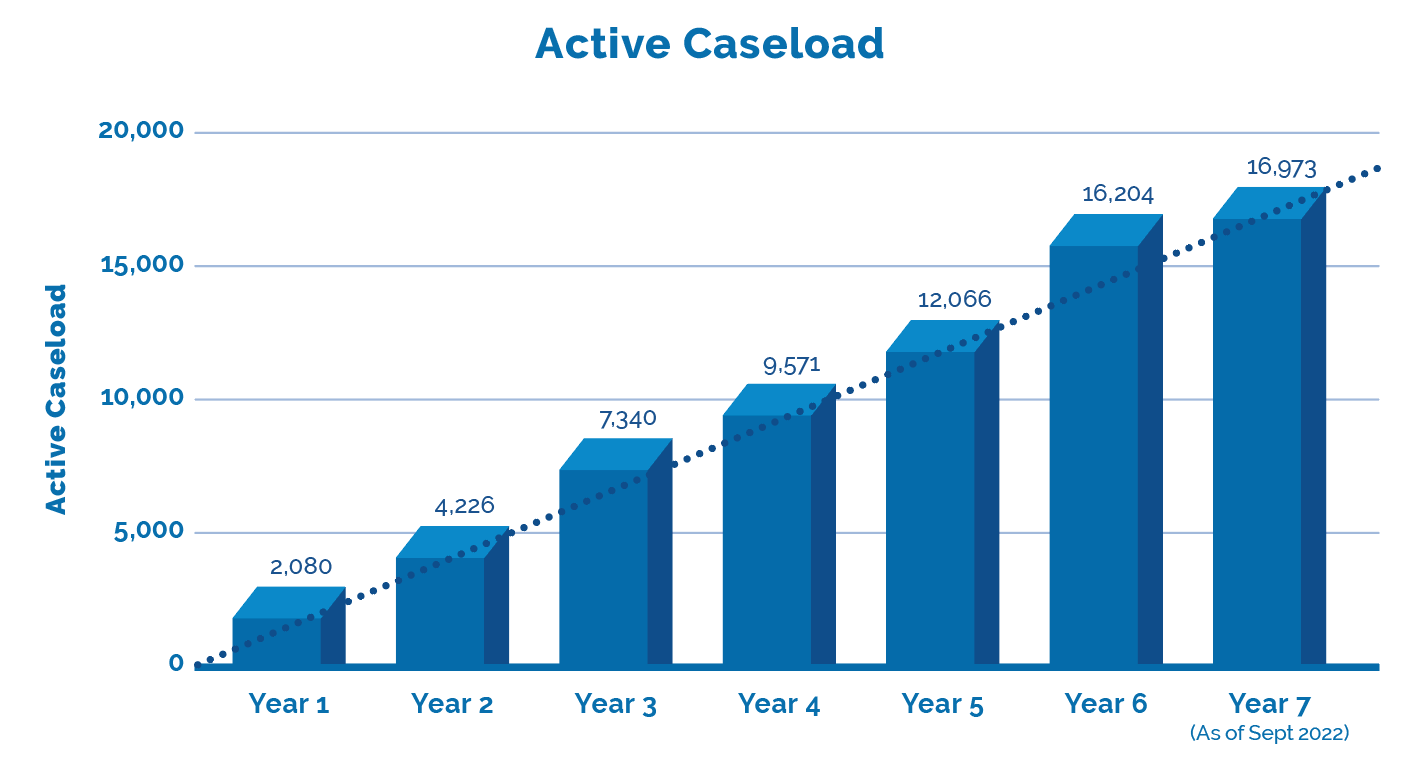

The LAT released Performance Stats up to mid-year 7 which is current through to the end of September 2022. Together with the LAT’s last update we can now provide a comparison of year over year, with projections through to the end of year 7 in this annual update. What difference did a year make?

1994 Claim Reopened Almost 20 Years Later Garners $85,000 Award

Maximum Award on 1994 Accident Claim, confirms the potential perils lurking in files that were not resolved on a full and final basis, even 20+ years later. In the specific circumstances of this matter, could that risk somehow have been anticipated?

Maximum Award on 1994 Accident Claim – The Applicant Shwaluk, injured in a July 1994 accident, received benefits for two – three years post accident, at which time her file was closed. Almost twenty years later, in November 2015, Shwaluk requested that her AB file be reopened.

Background

In 20-000137 v Royal & Sun Alliance Insurance (RSA), It was alleged that impairments caused by the subject accident had never resolved and had in fact worsened. For their part, RSA firstly claimed there to be no causal connection between the accident and the treatment being sought, and later relied upon medical evidence provided during the insurer’s examinations (IEs).

The Claim

After the file was reopened, Shwaluk ultimately sought entitlement to supervisory care level of attendant care benefits (“ACB”) of $3,000.00 per month (plus indexation) from November 21, 2022 She also sought determination as to the amount of ACB payable from April 2020 through to November 2022, including indexation. It was agreed herein that there was no dispute as to whether Shwaluk required ACB, rather a matter as to the type and quantum of same. The ACB was provided by Shwaluk’s husband, which was permitted under the Schedule as it read in 1994. There was in addition, a claim for six OCF18s for both physical and psychological therapy from November 2017 through to March 2021.

Conversion Disorder

Following the accident, Shwaluk began almost immediately to experience tremors, with these symptoms persisting post accident. The tremors worsened to the extent that she required almost around the clock assistance from her mother to tend to the home and children. She was off work until January 1995, however upon her return the tremors and related symptoms never resolved, contending that she was only able to continue working was because she was “strong willed” and wanting to be “normal.” In November 1995 she lost her job due to downsizing, however, was able to secure alternative employment with HSBC in 1997, with tremors though continuing. Ultimately however, in 2015 she began regularly experiencing a “brain fog” that caused performance issues at HSBC and eventually contributed to her leaving the company.

Shwaluk testified that she continually sought treatment and attended upon medical specialists, in order to secure a diagnosis and treatment for the tremors, that seemed to have no neurological basis. Finally in late 2016, she was “diagnosed with conversion disorder, also known as a functional neurologic disorder. This condition is marked by uncontrollable neurological symptoms (such as the applicant’s tremors and pain) that cannot be explained by a neurological disease or other medical condition.”

Insurer’s Expert’s

RSA relied upon the opinion of Dr. Sivasubramanian, who criticized Shwaluk’s expert who found there to be a need for supervisory care, relying upon “safety, motivational impairment, and comfort concepts.” He opined to be “ not aware of any clinical studies that supported such philosophies or the use of attendant care for treating conversion disorder.” He was of the opinion that Shwaluk’s care could be satisfied with five hours per week of care, as she “could prioritize how those five hours would be spent, which would allow for an attendant care service provider to follow a set schedule.” The Tribunal did not accept the premise of Dr. Sivasubramanian, given that he “devoted just a single short paragraph to his recommendation of five hours of attendant care, and provided no specific rationale therein as to how or why he came to that conclusion”.

RSA further relied upon the opinion of a neurologist, Dr. Angel, who spoke to the observed tremors as movements being a “functional tremor” or a “psychogenetic tremor,” meaning that the tremors were not caused by an organic neurological issue like a brain injury. Further, that Shwaluk “should have no difficulties with daily life, and that she needed to be more active and relax in the knowledge that her “brain is healthy.” The Tribunal though found that Dr. Angel “did not address the diagnosis of conversion disorder in his testimony or report… he did not review any of the medical documentation relating to this diagnosis. Dr. Angel seemed somewhat dismissive about this condition in his testimony, in my opinion, noting that there was an element of suggestibility to the applicant’s tremors. The conclusions reached by Dr. Angel were found “unrealistic, and that he failed to specify how the applicant would adopt these new approaches and activities without the assistance of supervisory attendant care and treatment, a sizeable gap in his assessment”.

Determination

The Tribunal found that Shwaluk “…is clearly suffering debilitating tremor attacks and connected physical and psychological issues that have dramatically changed her life. These impairments have rendered it impossible for her to continue to hold a job, and have virtually confined her to her home and the around-the-clock care of her husband who has been acting as her attendant care attendant since at least 2018″.

Ultimately the Tribunal agreed with Shwaluk’s experts who “supported supervisory care as opposed to scheduled attendant care services for one primary reason—the applicant’s tremors were unpredictable. I agree with them that it would be impossible to schedule attendant care in this situation, as the applicant could encounter tremors at any time that could put her personal safety and security at risk.

Therefore, Shwaluk was entitled to in excess of $150,000 in ACB from April 2020 through to November 2022, said total representing the maximum available $3,000 per month, with the required annual indexation plus interest. This care was confirmed as having been provided by her husband. On a going forward basis, entitlement for the remainder of 2022 indexed represented $5,054.64/month, to be recalculated each January 1 to account for ongoing indexation.

With respect to the six treatment plans, the Tribunal essentially relied upon the same evidence, noting however that a fair reading of the evidence suggested there to be relative consensus of all experts that there was required both physical and psychological care, although RSA did suggest that they did not accept the “specifics” of the contested items. All six were accordingly found to be payable. The Tribunal then concluded by considering Shwaluk’s claim for an award.

Causation

Shwaluk contended that RSA “denied benefits for years following the reopening of her claim in 2015 based on an allegation that the current impairments had not been proven to be causally connected to the accident in 1994. The applicant argues that causation was never challenged by the respondent in 1994, and that log notes and medical records from 1994 through 1996 demonstrate that the respondent was aware of the applicant’s impairments at that time.” For their part, RSA took the position that they were “unaware of developments with the applicant between 1994 and 2015, when the file was reopened. The respondent submitted that it followed the medical evidence, that the applicant had been working full time during most of the time between 1994 and 2015.”

The Tribunal “favour(ed) the applicant’s argument that causation was not a valid reason for the denial of the applicant’s claimed entitlements. I further agree with the applicant’s argument that the causation issue was not disputed in 1994-1995 during the initial handling of this file, and that this rationale was improperly used to withhold benefits from the applicant. The applicant demonstrated a consistent and continuous pattern of symptoms from 1994 to the time that she reopened her claim in 2015, evidence that should have been addressed in a much more comprehensive and timelier fashion than just denying on the basis of causation.”

It was noted that “Reliance on causation to deny benefits began with the first correspondence from the insurer to the applicant’s original counsel at the end of 2015… A continued general reliance on causation is shown in correspondence from the insurer to the applicant throughout 2016. Causation is also used as a primary reason to deny each of the six treatment plans in dispute here from 2017 through 2021.The insurer adds regular references to how long ago the accident occurred along with notations that there seems to be no causal link between the injuries from the subject accident and the recommended treatment plans.”

Award

The Tribunal found that RSA “…did not take into account the 1994-1996 medical records on this file when it was reopened in 2015. The applicant reported the same symptoms in 2015 that she reported in 1994, albeit to a worsening degree that had caused an impairment. The insurer did not contest that these 1994-1996 symptoms were caused by the accident at the time that this claim was first adjusted… As there was no basis for even this initial denial of the revived claim due to causation, this should have prompted a more proper investigation of the medical merits of the claim—not a new reason for denial that had never apparently been raised before.”

The Tribunal further found that “the insurer had at least four years to look into this file since it was reopened in 2015. It is inexcusable that the same causation argument was being made in 2020 that was made in 2015.” While the circumstances did suggest that a delay would not be unreasonable “I cannot overlook how the insurance company took so many years to finally do away with the causation argument. The insurer’s continued reliance on causation in denial letter after denial letter from 2015 to 2020 speaks to more than just a need to take time to assess all of the issues, or even to an honest misunderstanding of the file’s complexities; it speaks to the insurer being excessive, imprudent, stubborn, inflexible, unyielding, and immoderate.”

The Tribunal awarded the maximum award of 50% on both the ACB as well as treatment plans, given the “the impact of such an improper refusal on the applicant and her inability to seek proper care for years, a delay that may very well have exacerbated her impairments”. The total award for ACB and medical was $84,965.

If you Have Read This Far…

Inform your position & present persuasive arguments. Include an Outcome Analysis Report (OAR) in your case evaluation complete with For/Against cases. Get an OAR – Available as a fee for service.

inHEALTH Keeps you LAT inFORMED With Access To:

1. LAT Compendium Database – a relational database of LAT and Divisional Court Decisions equipped with multiple search options, Smart Filters, and concise case summaries

2. Notifications: – weekly LAT inFORMER delivered to your inbox Wednesdays; Newly Added Decisions on Fridays and Breaking News as and when it happens

3. Research Support: – inHEALTH’s Live Chat Experts for guided searches and technical inquiries.

Sign up for a 14 day free trial below to experience the service and see how it can help guide your decision making.